Black and missing in America: advocates call for more help

CBC News

Meagan Fitzpatrick

April 9, 2015

Derrick Butler has good days and bad days when it comes to the emotional roller coaster of dealing with missing loved ones. Sadness, frustration, anger, he feels them all.

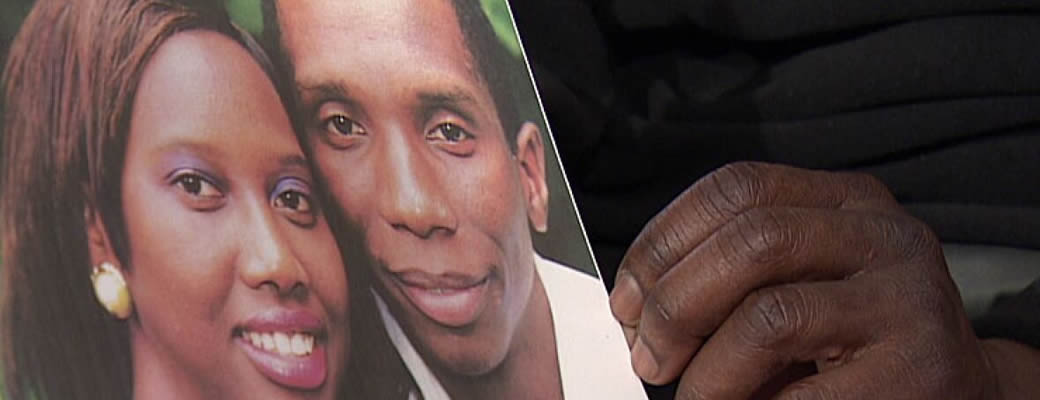

He’s been coping with the pain since February 2009 when his sister, Pamela, 47 at the time, mysteriously disappeared from her home in Washington, D.C. Her family suspects she was murdered by the man she was dating. Her body hasn’t been found, and no charges have been laid.

“My mother is taking this really hard,” Butler told CBC News. “Parents don’t look to outlive their kids.”

Local media covered the case, but no national attention was paid to it. No Dateline specials or network coverage. Butler says there is one reason for that: his sister is a black woman.

“That’s exactly what it is,” he replied when asked if racism figures into the level of media coverage of missing black Americans compared to their white counterparts.

Natalee Holloway, for example, was a blonde-haired, blue-eyed American teenager who went missing in Aruba in 2005. Her disappearance made not just national, but international headlines. She became a household name. Pamela Butler did not.

This past fall, a white college student in Virginia named Hannah Graham went missing and the story received substantial coverage on CNN and other networks. There are many examples like Holloway and Graham, as well as many missing black women whose names will never be known to the rest of the country.

Thousands of people are reported missing every year in the U.S. And while not every case will get widespread media attention, Butler and other advocates say the coverage of white and black victims is far from proportionate.

The latest statistics from the FBI indicate that 635,155 missing person reports were entered into its database in 2014. Of those, more than a third were African-Americans.

Raising awareness

Butler said police worked hard on his sister’s case, but families like his need more help from the media.

“We can’t get the word out by ourselves. I can walk the streets for another seven years and not get the word out as much as the media could get it out in one night,” he said.

Getting the word out about missing black Americans and other minorities is what Derrica Wilson and her sister-in-law Natalie are attempting to do with the non-profit organization they created in 2008.

Derrica Wilson said that she was motivated to start the Black and Missing Foundation after a young woman, Tamika Huston, disappeared from her hometown in Spartanburg, South Carolina in 2004.

Her family struggled to generate media attention. Then a year later when Holloway went missing and her story dominated headlines, Wilson was struck by the imbalance.

A former police officer in the Washington area, Wilson felt she needed to do something. Too many black people’s stories were “swept under the rug.”

“We wanted to even the playing field for all persons, because it’s not a white issue, it’s not a black issue, it’s an American issue,” Wilson said.

Helping families is ‘a calling’

In addition to media coverage, what is also an issue here is the way these cases are treated by law enforcement, said Wilson. Young black people are too often characterized as runaways, and missing African-American adults are often given short shrift because it is felt they might be engaged in criminal activity, she said.

When Hannah Graham went missing last fall in Charlottesville, Va., Wilson said she watched the police chief get emotional at news conferences.

It was painful to watch, she said, because Dashad Smith, a 19-year-old from the same community — black and transgendered — has been missing for two years and hasn’t been given the same kind of attention from police according to Wilson.

Police spokesman Gary Pleasants responded in an email that the two cases were treated differently — but by the national media “not by us.”

He said the police did hold news conferences on the Smith case and appealed to the public for help, but only local media showed up and there was no national interest.

News conferences were more frequent with the Graham case, he said, because the national media descended on Charlottesville and because new information came in daily that the police reported.

“We treat every missing person on the merits of the case and on what information we can gather. We do not look at their race, sex or anything else in determining how much effort we put into the case,” said Pleasants.

Smith’s grandmother contacted the Black and Missing Foundation for help. “Hannah’s mother and Dashad’s grandmother, they don’t feel any different. They both have someone who is missing, their heart feels the same way,” said Wilson.

Wilson says she in no way means to denigrate cases like Hannah Graham’s. All deserve attention. (Graham’s remains were found and a man has been charged with her murder.) Butler also echoed that sentiment when speaking about his sister’s case, saying he just wants an even playing field.

Wilson estimates the Black and Missing Foundation has helped more than 130 families find their missing loved ones alive. After an appearance on The View, a day-time talk show on ABC, a few years ago, tips about one woman came into the foundation and she was found alive.

So national media attention can be crucial.

Wilson and her sister have full-time jobs, spouses and children, and somehow make time to run the Black and Missing Foundation on top of those responsibilities. They try to build relationships with the media and law enforcement, and help give families tools and coping strategies to help find their loved ones.

“It’s a calling,” Wilson said. “I do not get a chance to often say that. I feel that everybody is placed on this Earth for a reason or a purpose and this is my purpose. If my child was missing I would want someone to do the same thing for my child.”

Photo credit: CBC News