How the media privileges white victims

The Seattle Times

Naomi Ishisaka

August 15, 2022

On the first slide is a picture of six white women and girls. The facilitator asks the room full of journalists of color if they know the names of the people pictured.

Without pause, the audience answers correctly Elizabeth Smart, Chandra Levy, Natalee Holloway, Caylee Anthony, Laci Peterson and Gabby Petito, some of the most well publicized missing or murdered women and girls from the past decades.

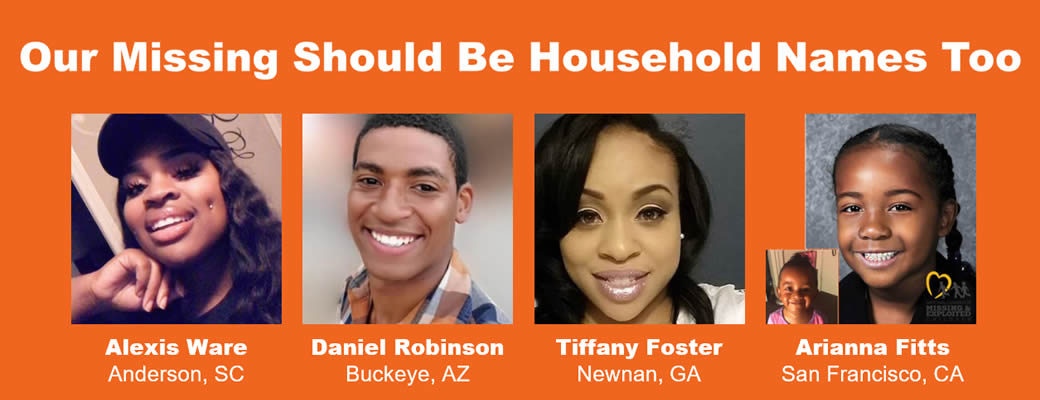

Next, they show slides with Black faces and ask the same question. Could anyone name three of the people pictured? Two? One?

Two people in the audience could identify one of the missing people pictured. No one could name two, much less three. The audience prize for anyone who could name three went ungifted.

This exercise by the Maryland-based Black and Missing Foundation at the National Association of Black Journalists and National Association of Hispanic Journalists convention in Las Vegas a little over a week ago illustrates a persistent problem that has devastating consequences: not every life matters equally when we go missing.

The “missing white woman syndrome” that Gwen Ifill described at the Unity: Journalists of Color convention in 2004 is still going strong.

A 2016 study from the Northwestern University Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology on the phenomenon found that Black people were “significantly underrepresented” in coverage of missing people they analyzed. A 2015 study from William & Mary found that Black children were 35% of missing children’s cases but made up only 7% of media coverage.

Natalie Wilson, co-founder of the 14-year-old Black and Missing Foundation, said the organization was born out of the realization that Black families they knew who had the same heartbreaking disappearances of their loved ones as white families were not getting anywhere near the same amount of attention.

The biases that lead to these disparities are deep rooted in our society, Wilson said. When a child of color goes missing, for example, they are more likely to be deemed a runaway, a police report is less likely to be taken and less attention will be focused on their case.

“What we’re finding is that race, income level, education, ZIP code — it’s often a barrier to media coverage, and law enforcement assistance, which really hampers the case … and it really impacts the individual being found,” Wilson said in an interview.

Worse, people who cause harm to vulnerable people know there will be less attention paid when victims are people of color and know they are more likely to be able to operate with impunity if they harm marginalized groups, she said.

Lack of diversity in newsrooms, as well, contributes to the empathy and coverage gap. If journalists can’t see themselves in other people’s experiences and don’t see victims as deserving of sympathy, they are less likely to see them as worthy of a story.

It’s also about who we see as born innocent and worthy of protection and who we see as guilty and fundamentally suspicious.

In a four-part HBO documentary on the organization called “Black and Missing,” Wilson highlighted the differences. “White women occupy a certain place in our society as the symbol of purity and the symbol of beauty and they deserve to be protected at all costs.”

This disparity impacts not just Black people, but Indigenous people, Latino people and other people of color as well. And while the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement garnered unprecedented attention in recent years, for example, we saw that once Gabby Petito’s tragic case became international news, all eyes went back to her.

While obviously a very different type of case, I have reflected on this dynamic in relation to Brittney Griner’s detention as well. I have been struck by the levels to which even people who I usually find to be empathetic and socially conscious, bend over backward to say she is getting what she deserves. “Why did she go to Russia in the first place?” “Why did she commit a crime if she didn’t want to end up in a penal colony?” “She’s rich and famous. Why should we care about her?” they ask.

But like the victims Black and Missing draws attention to, the lack of compassion for Griner is colored by race, sex, and in her case, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Despite protestations to the contrary, I think if athletes like Tom Brady or even Sue Bird were locked in a Russian cage on international TV, there would be daily vigils, campaigns and worldwide outcry calling for their immediate release.

Whether we acknowledge it or not, our perception of who deserves care and safety mirrors who we see as valuable in our society.

Vince Warren, the executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, said in the documentary if it weren’t for people like Wilson and co-founder and sister-in-law Derrica Wilson championing this effort, there would be little progress.

“We have developed entire structures around the concept of missing white people,” he said. “And we have virtually nothing except for the spit and grit of Black folks who are determined that our people matter too, that our bodies are not disposable, that our families deserve to be together.”

Photo credit: Black and Missing Foundation, Inc.